How COVID-19 Reshaped the Office Furniture Industry Overnight

Like most reviews sites, our editorial staff and laboratory testing expenses are partially offset by earning small commissions (at no cost to you) when you purchase something through those links. Learn More

Who will be the biggest winners and losers after the pandemic?

[Editors Note: This article has been updated as of 12/21/20.]

As impending coronavirus lockdown orders dominated the news on February 18th, 2020, the bloodbath on Wall Street began. The traditional commercial office furniture manufacturing sector was one of the worst hit, and still slowest to recover, after shutting down factories, cutting salaries, and laying off thousands of workers.

Stock values for these companies have been hammered as badly as the airlines, and far worse than the averages for the respective stock exchanges they belong to. Those with strong enough balance sheets will either weather the storm until things return back to “normal,” (whatever that’s going to be) while others will attempt to adapt to unprecedented tectonic shifts in their businesses.

One trend that is clear, is that sales of office furniture through their traditional “contract dealers” channel, which was already in slow decline well before the pandemic, has even more rapidly shifted towards direct-to-consumer (DTC) channels—a.k.a. e-commerce. Acquisition of ecommerce companies is one way some of these furniture behemoths are dealing with the problem, such as when Cathay Capital-backed Innovative Office Products acquired Kickstarter success story StandDesk.co in August and Kimball International (owner of National Furniture brands) acquired Poppin.com for $110M+ in November of 2020.

Many of the middle-market companies without the resources to acquire offsetting businesses or the ability to pivot quickly to e-commerce on their own are considering whether to fire sale their businesses or liquidate them, as many companies in the sector are reporting new orders down 35 -50 percent and struggling with negative cash flow. Even some publicly-traded manufacturers, like Inscape Corporation (INQ:TO), have been dealt a body blow after several years of decline before COVID-19 hit, with their stock trading well below a dollar now.

Let’s face it: Few organizations are currently thinking about major office expansion or remodeling projects; employers’ immediate focus is on getting all of their home-bound office workers as productive as possible, as quickly and inexpensively as possible. Most OEM manufacturers we spoke with in late Q4, 2020 have indicated that they have no major “project” orders in the pipeline for large enterprise expansion or remodeling projects in 2021; all have been shifted out to 2022 despite good news on the emergency vaccine approvals that came last week.

How Employers Have Adapted

Many employers immediately started offering $200 – $2,000 expense reimbursements for any new equipment their workers will need to buy in order to become as productive working from home as they were in the office. The average reported stipend for home office upgrading appears to be around $1,000.

Employers are increasingly becoming cognizant of the fact that workers can’t be left to work from home on lousy, non-ergonomic desk setups for a year or more, as documented in this University of Cincinnati Ergonomics Department study of 843 staffers who were all ordered home back in the spring of 2020.

As a consequence, standing desk sales are brisker than ever — online. The thing is that few of these desks are being purchased from the traditional contract furniture manufacturers and dealers who likely outfitted the desk they used to sit at in the office.

The Democratization of Office Furniture Acquisition

Before the pandemic, office furniture purchasing decisions were typically made by a small committee of people, including facilities managers, architects and interior designers, HR and Finance representatives. These purchases were ordinarily pushed through as large capital equipment “projects,” with the furniture depreciated over five to ten years. In a tectonic shift that has essentially democratized the purchasing of office furniture, the vast majority of new standing desks are now being purchased directly by the employee, and then being partially or fully reimbursed by the employer (“expensed” rather than “capitalized,” in accounting lingo).

Taking this decision out of the hands of a small committee and distributing it to each employee allows workers the option of choosing a desk that nicely fits their home office space and decor, rather than their corporate office look. Some are using the subsidy to upgrade to something even nicer than they would have otherwise gotten, if only to win some brownie points with the spouse.

For the most part these employees are shopping online to find something that suits their home, and perhaps more importantly, their assembly skills. Contract furniture, after all, is designed for professional installers to put together. They don’t exactly have friendly video instructions, pre-drilled pilot holes or even robust packaging to survive being shipped individually. Nor, anything to offer like the tools-free, quick-install standing desks that have become increasingly popular online options.

The polls are in

Many major employers have already announced that they expect one-half to two-thirds of their desk workers to remain “WFH” indefinitely now. A study by IBM of 25,000 office workers found that 54 percent of desk workers want to continue to work from home full time, and 75 percent would like to do so part time. Forty percent felt that their employers should at least offer the option of working remotely, and we now see companies like Facebook even promoting the idea that some of their employees should move to cities with a lower cost of living, and backing it up with moving allowances.

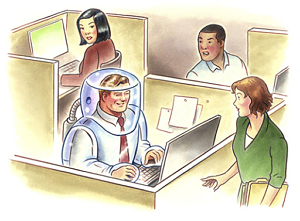

Even before COVID-19, some 43 percent of American workers were already working from home at least part time. The pandemic merely forced everyone else — from the call center to C-suite executives — to jump into the pool and find out that the water is just fine, if just a little cold at first. Once they got their hi-res webcams and hi-fidelity headsets working, they quickly became expert at dressing for business from the waist up for their daily Zoom conferences.

Hindsight being 20/20, it is now apparent that the traditional office plan espoused by the commercial office furniture industry and embraced by employers made it easier for workplaces to become hotbeds for spreading colds, the flu and viruses like COVID-19.

In what should have raised great alarm when it was first published in 2014, a Norwegian study on sick leave rates among workers in open office plan provided ample scientific proof that workers in such close proximity were far more prone to catch colds and influenza from each other. Instead, this report was flatly ignored. Profits came before health. Only now we know that in the long run, in the age of the pandemic, profits and employee health are inextricably tied to one another.

While no one accuses these office furniture manufacturers, architects and interior designers of malicious intent, it is now obvious that the “open space plan” they have promulgated heavily for the past thirty years has unwittingly become a major contributor to the ease with which the Coronavirus — among other diseases — have been able to spread so quickly within the US work force. To be fair, employers who kept buying into the open office plan share in some of the responsibility here.

How did we even get here?

The “cubicle farm” was never the intent of Herman Miller designer Robert Propst when he introduced the concept of “Action Office” in the 1960s.

Propst had envisioned a radical departure from the massive rooms of evenly spaced rows and columns of wooden or steel desks that were the hallmark of efficient office facilities during the first half of the 19th century.

Only those with executive status had the coveted private offices away from the hustle and bustle of typewriters, cigarette smoke and telephone calls that characterized a busy open office — and as a result of that privacy, they were more productive than the common worker bee.

Ahead of his time, Propst envisioned an office layout that relied on lightweight sitting and standing desks, filing systems and comfortable seating areas. Acoustical panels helped insulate workers from the noise of telephone calls and typing.

At the end of the day, the concept of a completely customizable workspace didn’t sit well with executives who didn’t value the individuality of their workers. The Action Office idea was adored by interior designers but sadly dismissed by just about everyone else.

Undeterred by the failure of his first concept, Propst went back to the lab and created the Action Office II. The new design took his acoustical panel concept to the next level. The panels became miniature walls of multiple heights that separated each space into its own office without completely isolating a worker off from their colleagues.

Lightweight and easier to assemble, the new cubicle designs made more sense to executives. (If you’ve ever had the dubious pleasure of working in one of these cube farms, you can undoubtedly recall the phenomenon of “gophering:” Peeping your head up over the 4-foot cubicle wall to shout over to other caged prisoners — erm, co-workers.)

But companies didn’t adopt Action Office II the way Propst intended, either. Which oddly didn’t stop copycat competitors. Instead of going for roomy desk spaces with different designs and walls of different heights, they opted for tiny, boxed-in desks instead.

The industry, vendors and customers both, basically ignored Propst’s vision of a flexible workspace and open visual sightlines. Using Propst’s brainchild, cubicles were used to cram even more workers into offices. The office he invented shrank and shrank until it became impersonal and crowded. The age of the cubicle farm began.

Years later Steve Jobs would adopt many of these concepts into his design of Apple Park headquarters (see below), but Propst sadly died long before his vision of the office of the future would take hold.

Eventually the industry had to give the cubicle a more euphemistic label; it is now known as a “wall system.” And some are still being sold and installed to this day, but for all intents and purposes the oft-derided cubicle farm has fallen out of favor, with the new “open plan” taking hold in an estimated 80 percent of US office spaces today.

Mr Gorbachev, tear down this cubicle wall!

OK, Reagan didn’t exactly that, but he might as well have. For the past three decades the open office concept has been touted as the be-all and end-all of workplace design to promote collaboration, increase productivity, and retain top talent.

First, you tear down the walls and dispense with the soulless cubicles. Then, you put everyone at long tables (a.k.a. “benching desks”), shoulder to shoulder, so that they can talk more easily. Ditch any remaining private offices, which only enforce the idea that some people are better than others, and seat your most senior employees in the mix.

Magically, your people will collaborate. Ideas will spark. Your staff will be more productive. Visitors will look at your office and think, This place has energy! Your company will create products unlike any the world has ever seen. It will be as famous and successful as Google and Facebook.

But a tome of research suggests that open offices have actually had the opposite of the intended effect. Instead of promoting more face-to-face interactions, a study by Harvard University found open offices promote 70 percent fewer, as employees opt instead for texting or email. Rather than increasing productivity, an Exeter University study found that productivity in open offices drops by 15 percent. A survey of 1,000 office workers by Bospar PR found 76 percent of workers hate open office plans because of factors such as noise and a lack of privacy.

Rather than boosting collaboration, they’ve actually been a huge failure in just about every measurable way. For as long as these floor plans have been in vogue, studies have debunked their purported benefits. Researchers have shown that people in open offices take nearly two-thirds more sick leave time and report greater job dissatisfaction, more stress, and less productivity than those with more privacy.

To help overcome these challenges with benching desks some companies have added $10,000 “phone booths” to their open space plans to provide workers with some quiet time for concentration, or just a place to make a quiet phone call. Many office workers are not big fans of these claustrophobic closets, feeling like they’re working in a fishbowl.

All of these shortfalls of the open office plan are well-established science at this point, which leaves companies with only a single reason to implement open plans: You can cram more people into a smaller space, thereby reducing the cost of office floor space — from 225 square feet per employee to 175.

But this can be a false economy because the cost of labor is higher than the cost of floor space. Therefore, even a 15 percent drop in productivity usually eats up any cost savings that might result.

That being said, there aren’t all that many alternatives. Cubicles provide a bit more privacy and a bit less noise, but they’re ugly and depressing. Workers prefer to work in private offices, but they can encourage stovepiping. And if they have to share their office with even one more colleague they might as well be sleeping in the same bed when it comes to sharing germs. The Norwegian study found they’d actually be better off in a cubicle or at a benching desk.

Touted as one of the most effective office space alternatives, the new Apple Park headquarters designed by Steve Jobs, consists of private offices surrounding a hub of common area that’s specifically designed for socializing. That design, however, involves at least twice as much floor space as traditional private office, and even still, workers relegated to open space workstations have already been revolting.

And now, it’s open germ warfare

In the age of the novel Coronavirus, we’ve all become painfully aware that an uncovered cough or sneeze creates a spray of up to 40,000 disease-ridden droplets that travel at up to 200 mph, to a distance of up to 26 feet, and stay suspended in the air for up to 10 minutes.

These droplets can make you ill if you breathe them in. Office walls, and to a lesser extent, cubicle walls, create barriers to these projectiles, lessening the chance that one sick worker will make other workers sick. If they don’t run into each other in the elevator, bathroom or cafeteria, that is.

These droplets can make you ill if you breathe them in. Office walls, and to a lesser extent, cubicle walls, create barriers to these projectiles, lessening the chance that one sick worker will make other workers sick. If they don’t run into each other in the elevator, bathroom or cafeteria, that is.

The big furniture companies that have been selling “benching desks” for all these years are now promoting silly notions like adding an acrylic barrier down the middle of the desks, already gaining the pejorative moniker of “sneeze guard.” This is pure social distancing theater, intended to give workers the feeling that their employers are taking active measures to reduce the spread of disease in their offices.

Medical experts are concerned, however, that these kinds of measures may actually risk workers becoming more complacent and dropping their masks while at their desks, or taking other measures at protecting themselves from each other’s aerosolized emissions of the virus.

Some companies have proposed having the cleaning crews upgrade their skills and solutions arsenals from “basic cleaning” to “detailed cleaning AND disinfecting,” and to scrub the office space every night instead of just once a week. Even if this were practical and affordable (it’s not, at least for most companies), spraying 70 percent-alcohol-based cleaning chemicals on every workstation, every night, will likely destroy computer keyboards and damage the furniture.

With rare exception, most office desks are not made with healthcare-grade laminates. They are made with high pressure laminates that will not only fade in color when repeatedly sprayed with these alcohol-based solutions, but will also lose the glue from the their edge seams, leading to the peeling off of edge banding and laminates over time. So this notion of nightly deep-cleaning of all the desks in an office is really just more post-pandemic theater.

So what does the future hold for the commercial office furniture industry?

If you tune into these companies’ quarterly earnings reports you’ll hear aspirational notions like “sure, companies will not renew all their leases but this will leave them more money to spend on nice new cubicles with really high walls,” or “companies will lease even more space and spread their employees further apart to increase social distancing, and they’ll need new furniture systems to meet these requirements.”

The only ones beating their chests are those with substantial online sales of residential furniture, especially chair products (usually from acquisitions prior to COVID-19, such as Herman Miller’s fortuitous acquisition of Design Within Reach in 2014), or those with very strong Asian business, where things do indeed seem to be “rapidly getting back to normal” for traditional office furniture manufacturers as compared to the Americas and Europe.

They explain that conference rooms built for 15 will have chairs removed so that only five people could use them at a time, properly distanced.

We get the aspiration to come out of the pandemic even stronger than when they went in. We just don’t know how many employers are going to feel so flush with cash after the recession.

The consensus among industry followers is that for the titan commercial furniture manufacturers, along with rafts of commercial architects and interior designers, contract furniture dealers and installers, there will be a dearth of new business for at least the next two to three years as most employees continue to stay working from home until things sort themselves out. Contract furniture dealers we have interviewed for this article — the proverbial “tip of the spear” for office furniture manufacturers — have reported anywhere from a 25 percent to 75 percent drop in business as of Q4, 2020. A stark indication of just how bad things are for the commercial dealer channel right now is that Contract Magazine has shuttered after 60 years in business.

The commercial office furniture industry has long taken a defensive posture that viewed e-commerce as the enemy. With the one exception of $1.3B Knoll, which acquired the pioneering ergonomics ecommerce player Fully.com in 2019. On Knoll’s Q1’20 earnings call management was quick to point out what a brilliant move that was, as without Fully’s booming e-commerce revenue the company as a whole would have booked much uglier financial results. That said, as can be seen in the stock chart above, Fully’s booming sales volumes are still a drop in the bucket in the context of Knoll’s overall global business.

Alas, most of Knoll’s peers have taken a wait-and-see approach, only a few of them acquiring any of Fully’s peers or launching their own office furniture e-commerce operations. Now, they’re probably all wishing they had — and before the pandemic hit.

What this all means for WFH

Judging from the sheer explosion of demand for standing desks since the lockdowns began, WFH is here to stay. Probably for decades. The problem for these contract furniture manufacturers is that their products were designed to be put together by professional installers, and they cost 2 – 3x more than what can be purchased online. The few products that they do offer for sale online are basically IKEA projects, and not something most employers are interested in saddling valued employees with the task of assembling on their own.

Manufacturers like iMovR have already figured out how to design desks that assemble in minutes with no tools (e.g. their Lander desk), and they manufacture them on-demand, to-order, perfectly matching the employee’s home office space and decor, and shipping out in only one week. Some are even manufactured with healthcare-grade 3D laminate that can withstand any cleaning and disinfecting solvents like the ones hospitals use to sanitize rooms.

Before the pandemic, the contract furniture manufacturers already ceded 60 percent of the market to e-commerce and retail. The numbers have yet to be tallied for post-pandemic times but we wouldn’t be surprised if there’s already been a tectonic movement to more like 80 percent/20 percent, as the home office becomes the main office for the majority of workers in Corporate America.

0 Comments

Leave a response >